Introduction

Picture this: you’re analyzing an Android application that’s sending encrypted traffic to suspicious servers. You’ve captured the packets, but they’re just gibberish—TLS encryption has turned everything into an unreadable stream of bytes. The app has no proxy settings to configure, certificate pinning blocks your MITM attempts, and traditional interception tools are useless. How do you peek inside?

This is the puzzle we set out to solve. The answer lies not in breaking the encryption, but in catching the keys before they’re used. Every TLS implementation must, at some point, have the session keys in memory. If we can find the exact moment when those keys are generated and hook into that function, we can extract them and decrypt the traffic at our leisure.

The challenge? Modern Android applications like Signal, Chrome, and Flutter apps don’t use the system’s TLS libraries. Instead, they bundle their own copy of BoringSSL (Google’s fork of OpenSSL) or rustls (a Rust TLS library), compiled directly into their native libraries. These libraries are “stripped”—compiled without debug symbols or function names—which means tools like friTap cannot hook the relevant functions by name. When I originally developed friTap, this was a significant limitation: the tool relies on symbol names to locate functions like SSL_read, SSL_write, and crucially ssl_log_secret. No symbols, no hooks.

In this post, we’ll walk through how to overcome this limitation, using Signal Messenger (version 7.52.2) as our example. Signal is an ideal case study because it bundles a statically linked, stripped rustls library—exactly the scenario where standard approaches fail. However, an important clarification: we’re extracting TLS transport keys, not Signal message keys. Signal uses end-to-end encryption via the Signal Protocol on top of TLS, so even with TLS keys, you’ll see encrypted Signal Protocol payloads, not plaintext messages. Decrypting actual Signal messages would require the Signal Protocol session keys, which is beyond the scope of this post. Our goal here is to demonstrate the technique for TLS key extraction from stripped binaries—a methodology that applies to any Android application with similar characteristics.

The Tool Ecosystem

Before diving in, let’s clarify the relationship between the tools we’ll use:

Frida

is a dynamic instrumentation framework that lets us inject JavaScript code into running processes. It’s the foundation everything else builds upon. Frida provides the Memory.scan() API that enables searching for byte patterns in process memory.

friTap is the TLS key extraction tool I developed to intercept session keys from various TLS libraries (OpenSSL, BoringSSL, GnuTLS, WolfSSL, NSS, rustls, and more). When symbols are available, friTap hooks functions by name. To overcome the stripped binary limitation, I added support for byte pattern matching—friTap can now locate functions by their instruction-level signatures when symbol names are unavailable.

BoringSecretHunter is a Ghidra-based analysis tool we developed to automate the extraction of byte patterns from stripped BoringSSL binaries. It also includes helper scripts for identifying and extracting target libraries from Android devices.

scanner.js is a Frida script (included in BoringSecretHunter) that performs kernel-level memory scanning to identify which libraries contain TLS functionality—essential when standard Frida APIs fail.

For more technical background on friTap, see this in-depth post or explore the source code directly on GitHub.

Prerequisites

To follow along with this guide, you’ll need:

On your Android device:

- A rooted device or emulator (required for Frida to attach to processes)

- Frida server installed and running (download from Frida releases , push to device, and run as root)

- USB debugging enabled in Developer Options

- The target application installed (we’ll use Signal Messenger)

On your computer:

- Python 3.x with pip

- Frida tools:

pip install frida-tools - friTap:

pip install friTap - Docker (for running BoringSecretHunter)

- ADB configured and able to connect to your device (

adb devicesshould show your device) - Wireshark for traffic analysis

- A packet capture tool (we’ll use

tcpdumpon the device or a network tap)

To verify Frida is working, run:

frida-ps -U

This should list all running processes on your Android device. If you see Signal in the list after launching it, you’re ready to proceed.

The Hunt for SSL Libraries: A Detective Story

Our investigation begins with a fundamental question: which library should we analyze? Applications like Signal ship multiple native libraries, and TLS functionality might be embedded in an unexpected location. What seems like a simple task—scanning loaded libraries for a telltale string—turned into a fascinating journey into how Android loads code from APKs.

The Goal

Before we can extract byte patterns, we need to find which library contains the TLS implementation. The key insight is that TLS libraries implementing the SSLKEYLOGFILE mechanism (a standard format for exporting session keys) contain characteristic string literals like CLIENT_RANDOM, EXPORTER_SECRET, or CLIENT_HANDSHAKE_TRAFFIC_SECRET. These strings are used as labels when logging keys—we’ll explore exactly how this works in the ssl_log_secret() section later. For now, the important point is: if we find CLIENT_RANDOM in a library’s memory, that library contains TLS key derivation code and becomes our target.

Our plan was simple: scan every loaded .so file in the Signal process for the string CLIENT_RANDOM.

First Attempt: The Standard Frida Approach

The textbook Frida approach uses Module.enumerateRanges() to get a list of memory segments for a specific library:

// The standard approach

const module = Process.findModuleByName("libsignal_jni.so");

const ranges = module.enumerateRanges('r--'); // Look for read-only data

console.log(`Found ${ranges.length} ranges for ${module.name}`);

ranges.forEach(range => {

Memory.scan(range.base, range.size, "434c49454e545f52414e444f4d", {

onMatch: (address) => console.log("Found CLIENT_RANDOM at", address)

});

});

The result was puzzling:

Found 0 ranges for libsignal_jni.so

Frida found the module object—it knew the base address and size—but when asked for memory ranges, it returned an empty list. It was as if libsignal_jni.so existed as a ghost: present in the process list, but occupying zero bytes of scannable memory.

The Investigation: How Android Really Loads Libraries

To understand why this happened, we had to dig into how the library got there in the first place. On a standard Linux system, when you call dlopen() on an ELF file (the executable format used by Linux and Android), the dynamic linker reads the file from disk, parses its ELF program headers, and uses mmap() to map the various segments (code, data, read-only data) into memory. Tools like Frida can then inspect /proc/self/maps and correlate entries with the original file to enumerate sections.

Since Android 6.0 (API level 23), apps can set android:extractNativeLibs="false"

in their manifest. When this flag is set, Android loads native libraries directly from inside the APK without extracting them to /data/app/.../lib/. This requires the .so files to be stored uncompressed and page-aligned (typically 4KB) within the APK—see the Android NDK documentation on packaging

for details. In /proc/maps, these mappings appear with paths like /data/app/.../base.apk!/lib/arm64-v8a/libsignal_jni.so, where the ! indicates the file is inside a ZIP archive.

Additionally, large frameworks like Chromium (and apps using WebView or Cronet) employ advanced linker techniques. For example, Chromium uses RELRO sharing to share the GNU_RELRO segment (read-only data after relocations) across processes via shared memory, significantly reducing per-process RSS. This involves custom logic in their Linker.java and native linker_jni.cc that creates memory mappings in non-standard ways.

The problem became clear: Frida’s Module.enumerateRanges() relies on matching file paths from /proc/maps against the module’s stored path. When a library is loaded from inside an APK, this matching breaks down. Looking at Frida’s gummodule-elf.c

implementation, we can trace the issue:

// gum_native_module_enumerate_ranges() iterates all process ranges

// and filters by path matching:

static gboolean

gum_emit_range_if_module_name_matches (const GumRangeDetails * details,

gpointer user_data)

{

GumEnumerateRangesContext * ctx = user_data;

// 1. If the memory range has no file backing, skip it.

if (details->file == NULL)

return TRUE;

// 2. THE FAILURE POINT

// It compares the path found in /proc/maps (details->file->path)

// with the path Frida thinks the module has (ctx->module->path).

if (strcmp (details->file->path, ctx->module->path) != 0)

return TRUE; // Paths don't match - skip this range!

return ctx->func (details, ctx->user_data);

}

This is the critical insight: gum_native_module_enumerate_ranges()

in the ELF backend actually calls the same underlying /proc/maps parser that Process.enumerateRanges() uses. However, it wraps this call with a strict filtering function (gum_emit_range_if_module_name_matches()

) that performs a naive strcmp() at line 422

. The problem is a path mismatch: when the kernel maps a library directly from an APK, /proc/maps shows the APK path (e.g., /data/app/.../base.apk), but the module’s stored path (obtained from the Android linker’s soinfo) includes the embedded file notation (e.g., /data/app/.../base.apk!/lib/arm64-v8a/libsignal_jni.so). The strcmp() never matches, so this filter rejects all valid memory ranges, resulting in an empty list.

The Solution: Ask the Kernel Directly

The key realization was that Module.enumerateRanges() and Process.enumerateRanges() both use the same underlying Linux /proc/maps parser—the difference is that Module.enumerateRanges() adds a path-matching filter that breaks for APK-loaded libraries, while Process.enumerateRanges() returns the raw kernel data without any filtering.

Looking at Frida’s gum_process_enumerate_ranges()

implementation on Linux (and Android):

// gum_proc_maps_iter_init_for_pid() at line 2237

void

gum_proc_maps_iter_init_for_pid (GumProcMapsIter * iter,

pid_t pid)

{

gchar path[31 + 1];

sprintf (path, "/proc/%u/maps", (guint) pid);

gum_proc_maps_iter_init_for_path (iter, path);

}

// The iterator opens the file directly (line 2251)

iter->fd = open (path, O_RDONLY | O_CLOEXEC);

// https://github.com/frida/frida-gum/blob/main/gum/backend-linux/gumprocess-linux.c#L1537C1-L1547C43

// and than parses each line 1537

...

sscanf (line,

"%" G_GINT64_MODIFIER "x-%" G_GINT64_MODIFIER "x "

"%4c "

"%" G_GINT64_MODIFIER "x %*s %" G_GINT64_MODIFIER "d"

"%n",

&range.base_address, &end,

perms,

&file.offset, &inode,

&length);

range.size = end - range.base_address;

...

This is the same parser that Module.enumerateRanges() uses internally. The difference is what happens next: Module.enumerateRanges() passes each result through the strcmp() filter shown above, while Process.enumerateRanges() returns the raw data directly to the caller. By using Process.enumerateRanges() and filtering by address range instead of file path, we bypass the broken path-matching logic entirely.

We switched to Process.enumerateRanges() instead of Module.enumerateRanges():

// The kernel-level approach

const module = Process.findModuleByName("libsignal_jni.so");

// 1. Ask the kernel for ALL readable memory

const allRanges = Process.enumerateRanges('r');

// 2. Filter to find ranges within our module's address space

const realRanges = allRanges.filter(range => {

return (range.base >= module.base) &&

(range.base < module.base.add(module.size));

});

// 3. Now scan these ranges for our target string

realRanges.forEach(range => {

Memory.scan(range.base, range.size, "434c49454e545f52414e444f4d", {

onMatch: (address) => console.log("Found at", address)

});

});

The difference was immediate. Where the standard API found 0 ranges, the kernel approach found 5 memory segments—the memory was there all along! We could see a large r-x (read-execute) segment containing the code and several r-- (read-only) segments containing data.

Automating Discovery with scanner.js

Based on this investigation, we developed scanner.js , a Frida script that performs kernel-level scanning across all loaded modules. Running it against Signal:

frida -U -n Signal -l scanner.js

Produces output like:

[-] Starting Kernel-Level Discovery Scan...

[+] CANDIDATE FOUND: libssl.so

|-- Match: "CLIENT_RANDOM"

|-- Segment: r--

|-- Address: 0x77cb0bfa5e

|-- Offset: 0x15a5e

|-- Path: /apex/com.android.conscrypt/lib64/libssl.so

[+] CANDIDATE FOUND: libconscrypt_jni.so

|-- Match: "CLIENT_RANDOM"

|-- Segment: r-x

|-- Address: 0x775f85b222

|-- Offset: 0x198222

|-- Path: /data/app/.../lib/arm64-v8a/libconscrypt_jni.so

[+] CANDIDATE FOUND: libsignal_jni.so

|-- Match: "CLIENT_RANDOM"

|-- Segment: r--

|-- Address: 0x77744a7d53

|-- Offset: 0x9fd53

|-- Path: /data/app/.../lib/arm64-v8a/libsignal_jni.so

[+] CANDIDATE FOUND: libringrtc_rffi.so

|-- Match: "CLIENT_RANDOM"

|-- Segment: r-x

|-- Address: 0x7744e87ff1

|-- Offset: 0x3aff1

|-- Path: /data/app/.../lib/arm64-v8a/libringrtc_rffi.so

[-] Scan Complete.

We found four libraries containing CLIENT_RANDOM: the system’s libssl.so and three app-specific libraries. For Signal, libsignal_jni.so is our primary target—it contains Signal’s core cryptographic functionality using a statically linked rustls implementation.

Lessons Learned

This investigation taught us several important principles. Abstractions leak: high-level APIs like Module.enumerateRanges() rely on parsing file metadata, and when loaders do unusual things (like mapping directly from a ZIP archive), that metadata may be unreliable or absent. Trust the kernel: when debugging memory issues, Process.enumerateRanges() (which reads /proc/maps) is the ultimate authority, showing what’s physically allocated regardless of what file headers claim. Scan everything readable: modern linkers often merge read-only data (.rodata) into executable (r-x) segments for efficiency, so limiting scans to r-- permissions might miss your target.

Extracting Libraries for Analysis

With our targets identified, we need to extract them from the device for static analysis. BoringSecretHunter includes findBoringSSLLibsOnAndroid.py, a helper script that connects to a running Android application via Frida, identifies libraries, and dumps them to disk.

First, clone the BoringSecretHunter repository:

git clone https://github.com/monkeywave/BoringSecretHunter.git

cd BoringSecretHunter

Running the script with just a package name searches for known BoringSSL patterns:

python3 findBoringSSLLibsOnAndroid.py --package org.thoughtcrime.securesms

This may only find system libraries like /apex/com.android.conscrypt/lib64/libssl.so, which isn’t helpful when an app bundles its own TLS implementation. To see all app-specific libraries, use the -L flag:

python3 findBoringSSLLibsOnAndroid.py --package org.thoughtcrime.securesms -L

This produces a complete listing:

================================================================================

App-Specific Libraries for: org.thoughtcrime.securesms

Total: 7 libraries

================================================================================

# Library Name Size Path

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 base.odex 21.3 MiB /data/app/.../oat/arm64/base.odex

2 libconscrypt_jni.so 2.0 MiB /data/app/.../lib/arm64-v8a/libconscrypt_jni.so

3 libsqlcipher.so 3.8 MiB /data/app/.../lib/arm64-v8a/libsqlcipher.so

4 libsignal_jni.so 6.6 MiB /data/app/.../lib/arm64-v8a/libsignal_jni.so

5 libaesgcm.so 84.0 KiB /data/app/.../lib/arm64-v8a/libaesgcm.so

6 libringrtc.so 2.6 MiB /data/app/.../lib/arm64-v8a/libringrtc.so

7 libringrtc_rffi.so 7.3 MiB /data/app/.../lib/arm64-v8a/libringrtc_rffi.so

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

To extract these libraries, add the -D flag:

python3 findBoringSSLLibsOnAndroid.py --package org.thoughtcrime.securesms -L -D

The libraries are saved to a dumps/ directory. Before running full Ghidra analysis, we can quickly verify which libraries contain TLS functionality using the strings command (a standard Unix tool that extracts printable strings from binary files):

for lib in dumps/*.so; do

echo "=== $lib ==="

strings "$lib" | grep -i "client_random"

done

This confirms libsignal_jni.so contains CLIENT_RANDOM, making it our target for pattern extraction.

Understanding the Target: ssl_log_secret()

Now that we have our target library, we need to understand what we’re looking for. The key to TLS key extraction lies in a function called ssl_log_secret(). Every major TLS implementation—BoringSSL, OpenSSL, rustls—implements support for the SSLKEYLOGFILE

mechanism, which allows TLS libraries to export session keys in a format that tools like Wireshark can use for decryption.

Looking at the BoringSSL source code , we can see how this function operates:

bool ssl_log_secret(const SSL *ssl, const char *label,

Span<const uint8_t> secret) {

if (ssl->ctx->keylog_callback == nullptr) {

return true;

}

// ... logging logic follows

}

The Span<const uint8_t> parameter is a C++ type representing a contiguous sequence of bytes—essentially a pointer plus a length, similar to a byte array or buffer containing the secret we are interested in.

Here’s the critical insight that makes our approach possible: ssl_log_secret() is always invoked during the TLS handshake, regardless of whether the SSLKEYLOGFILE environment variable is set or a keylog callback is registered. The function is called unconditionally; the decision about whether to actually log the keys happens inside the function by checking if a callback exists. This means we can hook ssl_log_secret() and intercept all TLS secrets as they flow through, capturing the key material before the conditional return.

During a TLS 1.3 handshake, the function tls13_derive_handshake_secrets() calls ssl_log_secret() multiple times with different labels. From the source code

:

bool tls13_derive_handshake_secrets(SSL_HANDSHAKE *hs) {

SSL *const ssl = hs->ssl;

if (!derive_secret(hs, &hs->client_handshake_secret,

kTLS13LabelClientHandshakeTraffic) ||

!ssl_log_secret(ssl, "CLIENT_HANDSHAKE_TRAFFIC_SECRET",

hs->client_handshake_secret) ||

!derive_secret(hs, &hs->server_handshake_secret,

kTLS13LabelServerHandshakeTraffic) ||

!ssl_log_secret(ssl, "SERVER_HANDSHAKE_TRAFFIC_SECRET",

hs->server_handshake_secret)) {

return false;

}

return true;

}

By hooking ssl_log_secret(), we intercept secrets with these labels:

For TLS 1.2:

CLIENT_RANDOMandMASTER_SECRET— the master secret derived from the key exchange

For TLS 1.3:

CLIENT_HANDSHAKE_TRAFFIC_SECRETandSERVER_HANDSHAKE_TRAFFIC_SECRET— used during the handshakeCLIENT_TRAFFIC_SECRET_0andSERVER_TRAFFIC_SECRET_0— used for application dataEXPORTER_SECRET— used for key derivation in certain protocols

This approach is library-dependent rather than OS or architecture-dependent. The same ssl_log_secret() function exists in BoringSSL whether compiled for ARM64, x86_64, or any other architecture, and whether running on Android, Linux, Windows, or macOS. What changes is the compiled byte representation, which is why we need architecture-specific patterns.

From Source Code to Assembly

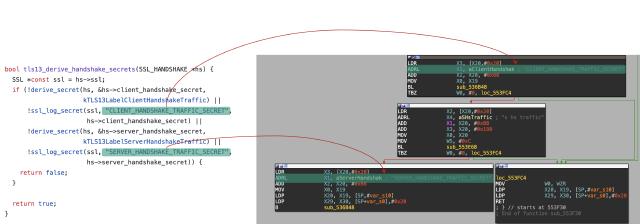

The following image illustrates how the source code maps to ARM64 assembly in a stripped binary:

Source code to ARM64 assembly mapping showing ssl_log_secret() invocations

The red arrows trace the connection between source code labels ("CLIENT_HANDSHAKE_TRAFFIC_SECRET", "SERVER_HANDSHAKE_TRAFFIC_SECRET") and the corresponding ARM64 assembly. The ADRL instructions load string pointers into registers, followed by BL (branch with link—ARM’s equivalent of a function call that saves the return address) instructions calling ssl_log_secret() (shown as sub_536B48 because the binary is stripped of symbol names). This visual mapping demonstrates why byte patterns work: even without symbols, the function’s structure—its prologue, register usage, and call pattern—remains consistent across builds.

Hooking via Byte Patterns

When functions have no names, we identify them by their fingerprint. friTap leverages Frida’s Memory.scan() API to search for specific instruction sequences that uniquely identify the ssl_log_secret() function. This works because compiled functions have characteristic prologues—the sequences of instructions at the start of a function that set up the stack frame, save registers, and prepare for execution. These prologues remain largely consistent across builds of the same library, even when optimization levels or minor code changes alter other parts.

The pattern extraction process used by BoringSecretHunter is guided by research on function fingerprinting, including FLIRT (Fast Library Identification and Recognition Technology), a signature-based system developed by Hex-Rays in 2004 for their IDA Pro disassembler. This research established that a signature of roughly 16–32 bytes from a function’s prologue is typically sufficient for unique identification.

BoringSecretHunter extracts patterns by starting at the function prologue and continuing until the first non-call branching instruction (such as a conditional jump). If this initial signature is shorter than 32 bytes, extraction continues until a subsequent branch. The resulting byte pattern, paired with its offset in the target library, enables precise identification at runtime.

You provide friTap with patterns using the --patterns <file.json> option. Patterns are organized by module name, platform, and architecture:

{

"modules": {

"libcronet.so": {

"android": {

"arm64": {

"Dump-Keys": {

"primary": "3F 23 03 D5 FF C3 01 D1 FD 7B 04 A9...",

"fallback": "FF 43 02 D1 FD 7B 05 A9 F8 5F 06 A9..."

}

}

}

}

}

}

Each pattern entry can define both a primary and a fallback pattern. friTap first attempts to match the primary pattern; if no match is found, it tries the fallback. This accommodates variations from different compiler versions, optimization settings, or minor library updates where the function prologue might differ slightly.

Currently, friTap implements pattern-based hooking for the Dump-Keys category, which targets ssl_log_secret(). For Android, friTap includes built-in patterns for common libraries like Cronet (libcronet.so, Google’s Chromium network stack used by many apps) and Flutter (libflutter.so). The technique works across all platforms Frida supports—Linux, Windows, macOS, iOS—making it broadly applicable.

Building BoringSecretHunter

BoringSecretHunter uses Ghidra (the NSA’s open-source reverse engineering tool) for binary analysis. To simplify setup, we provide a Docker image that includes Ghidra and all dependencies:

cd BoringSecretHunter

docker build -t boringsecrethunter .

The build takes a few minutes as it downloads and configures Ghidra. Once complete, you’ll have a self-contained analysis environment.

Analyzing Signal with BoringSecretHunter

With our target library extracted and BoringSecretHunter ready, we can extract the byte patterns. First, create the required directories and copy the library:

mkdir -p binary results

cp dumps/libsignal_jni.so binary/

Then run the analysis:

docker run --rm \

-v "$(pwd)/binary":/usr/local/src/binaries \

-v "$(pwd)/results":/host_output \

-e DEBUG_RUN=true \

boringsecrethunter

The analysis takes several minutes as Ghidra decompiles the binary. Here’s the key output:

Analyzing libsignal_jni.so...

BoringSecretHunter

Identifying the ssl_log_secret() function for extracting key material using Frida.

Version: 1.0.6 by Daniel Baier

[*] Start analyzing binary libsignal_jni.so (CPU Architecture: ARM64). This might take a while ...

[*] Looking for EXPORTER_SECRET

[*] Found 0 function(s) using the string: EXPORTER_SECRET

[*] Trying fallback approach with String CLIENT_RANDOM

The tool first searches for EXPORTER_SECRET in the binary’s .rodata section (read-only data, where string literals are stored). When direct string references aren’t found (often the case with stripped binaries), it falls back to searching for hex patterns and tracing cross-references (places in the code that reference a particular address or string).

[*] Searching for hex representation of: EXPORTER_SECRET

[*] Found pattern: 45 58 50 4F 52 54 45 52 5F 53 45 43 52 45 54 00 at: 001e4731 (IDA: 0x000E4731)

[*] String found in .rodata section at address: 001e4731

[*] Found reference to .rodata at 006540a8 (IDA: 0x005540A8) in function: FUN_00653fd4

[*] Analyzing reference at address: 006540a8 in function: FUN_00653fd4

[!] Start analyzing the function at ref: FUN_00653fd4

[!] Target address is part of the analyzed function

[*] Function label: FUN_00636b48 (FUN_00636b48)

[*] Function offset (Ghidra): 00636B48 (0x00636B48)

[*] Function offset (IDA with base 0x0): 00536B48 (0x00536B48)

[*] Byte pattern for frida (friTap): FF 43 02 D1 FD 7B 05 A9 F7 33 00 F9 F6 57 07 A9 F4 4F 08 A9 FD 43 01 91 57 D0 3B D5 E8 16 40 F9 A8 83 1F F8 08 34 40 F9 08 11 41 F9 08 08 00 B4

Note the two different offsets: Ghidra uses a base address of 0x100000 by default, while IDA Pro uses 0x0. If you want to verify the patterns manually in your disassembler, use the appropriate offset for your tool.

The analysis continues, detecting that this is actually a Rust binary using rustls:

[*] Target binary is a Rust binary. Looking if RusTLS was used...

[*] Found pattern: 72 75 73 74 6C 73 at: 001d2543 (IDA: 0x000D2543)

[*] RusTLS detected. Try using the RusTLS hooks!

[*] Previous pattern was only a TLS 1.3 pattern. Now looking for the TLS 1.2 pattern...

[*] Found pattern: 6D 61 73 74 65 72 20 73 65 63 72 65 74 00 at: 001f1668 (IDA: 0x000F1668)

[*] Found reference to .rodata at 00650468 (IDA: 0x00550468) in function: FUN_00650414

[*] TLS 1.2 RusTLS:

[*] Function label: FUN_0064e9ec (FUN_0064e9ec)

[*] Function offset (Ghidra): 0064E9EC (0x0064E9EC)

[*] Function offset (IDA with base 0x0): 0054E9EC (0x0054E9EC)

[*] Byte pattern for frida (friTap): FF 83 01 D1 FD 7B 03 A9 F6 57 04 A9 F4 4F 05 A9 FD C3 00 91 56 D0 3B D5 F5 03 00 AA E0 23 00 91 C8 16 40 F9 F3 03 02 AA F4 03 01 AA A8 83 1F F8 6D A9 00 94

[*] TLS 1.3 RusTLS:

[*] Function label: FUN_00636b48 (FUN_00636b48)

[*] Function offset (Ghidra): 00636B48 (0x00636B48)

[*] Function offset (IDA with base 0x0): 00536B48 (0x00536B48)

[*] Byte pattern for frida (friTap): FF 43 02 D1 FD 7B 05 A9 F7 33 00 F9 F6 57 07 A9 F4 4F 08 A9 FD 43 01 91 57 D0 3B D5 E8 16 40 F9 A8 83 1F F8 08 34 40 F9 08 11 41 F9 08 08 00 B4

[*] This binary contains RusTLS - try to use the RusTLS hooks for this pattern!

=== Finished analyzing libsignal_jni.so ===

BoringSecretHunter provides separate patterns for TLS 1.2 (which uses MASTER_SECRET) and TLS 1.3 (which uses the various traffic secrets). We now have everything needed to create our pattern file.

Using Patterns with friTap

With the extracted patterns, we create a JSON pattern file. The TLS 1.3 pattern becomes our primary (since most modern connections use TLS 1.3), and the TLS 1.2 pattern becomes the fallback:

{

"modules": {

"libsignal_jni.so": {

"android": {

"arm64": {

"Dump-Keys": {

"primary": "FF 43 02 D1 FD 7B 05 A9 F7 33 00 F9 F6 57 07 A9 F4 4F 08 A9 FD 43 01 91 57 D0 3B D5 E8 16 40 F9 A8 83 1F F8 08 34 40 F9 08 11 41 F9 08 08 00 B4",

"fallback": "FF 83 01 D1 FD 7B 03 A9 F6 57 04 A9 F4 4F 05 A9 FD C3 00 91 56 D0 3B D5 F5 03 00 AA E0 23 00 91 C8 16 40 F9 F3 03 02 AA F4 03 01 AA A8 83 1F F8 6D A9 00 94"

}

}

}

}

}

}

Save this as signal_pattern.json. Make sure Signal is running on your device (launch it if it isn’t), then run friTap:

fritap -m -v -k signal_keys.log --patterns signal_pattern.json org.thoughtcrime.securesms

The flags:

-m: Target a mobile (Android/iOS) device via USB-v: Verbose output to see extracted keys in real-time-k signal_keys.log: Write keys to this file in SSLKEYLOGFILE format--patterns signal_pattern.json: Use our custom pattern fileorg.thoughtcrime.securesms: Signal’s package name

When successful, you’ll see:

[*] libsignal_jni.so found & will be hooked on Android!

[*] Pattern found at (primary_pattern) address: 0x6d82648b0c on libsignal_jni.so

[*] Pattern-based hooks installed.

[*] invoking keylog_callback from OpenSSL_BoringSSL

[*] CLIENT_HANDSHAKE_TRAFFIC_SECRET 65042333FEE2F43777A8B3AE7C26413CA7E15C1663D0447819D9D8441FDE6BA1 F2E8000B7C855ED3B2FFEC664C196438AD5A35E0A6FAF8B7F12175C723CF5422

[*] SERVER_HANDSHAKE_TRAFFIC_SECRET 65042333FEE2F43777A8B3AE7C26413CA7E15C1663D0447819D9D8441FDE6BA1 4501F2E426F06B6F8731C50A8C08832A7580D14910FE2A3238B601C3177CBD3C

[*] CLIENT_TRAFFIC_SECRET_0 65042333FEE2F43777A8B3AE7C26413CA7E15C1663D0447819D9D8441FDE6BA1 77597112752DA935D39FD610A0854904D0319831D867B87A7251896A18CBB5A5

[*] SERVER_TRAFFIC_SECRET_0 65042333FEE2F43777A8B3AE7C26413CA7E15C1663D0447819D9D8441FDE6BA1 6406815DFF7649F5E20D5052AAE62C72FC12A726616E2821DED3EC2A855DF600

[*] EXPORTER_SECRET 65042333FEE2F43777A8B3AE7C26413CA7E15C1663D0447819D9D8441FDE6BA1 CC9F3EA0FF5D60D8FC19010FA25E5F8EA31794C05109C01FD65106CDD5A3366A

Each line shows a secret type, the client random (a unique identifier for this TLS session), and the actual secret value. The extracted keys are written to signal_keys.log in SSLKEYLOGFILE format.

Video Demonstration

The following video demonstrates friTap extracting TLS keys from Signal Messenger in real-time:

Capturing and Decrypting Traffic

Extracting keys is only half the puzzle—we also need the encrypted traffic itself. There are several approaches:

On-device packet capture using tcpdump (requires root):

adb shell "su -c 'tcpdump -i any -w /sdcard/capture.pcap'"

# ... use the app to generate traffic ...

# Ctrl+C to stop

adb pull /sdcard/capture.pcap

Network-level capture using a WiFi access point you control, a network tap, or routing traffic through a capture host.

Proxy with friTap’s built-in PCAP support:

fritap -m -p capture.pcap -f -k signal_keys.log --patterns signal_pattern.json org.thoughtcrime.securesms

The -p capture.pcap flag tells friTap to also capture network traffic. The -f flag ensure we are doing a full packet capture (the default ports of adb and frida are filtered out).

Once you have both the capture file and the keys, open them in Wireshark.

wireshark capture.pcap

Then go to Edit → Preferences → Protocols → TLS, then set “(Pre)-Master-Secret log filename” to your key file path.

Wireshark will automatically match keys to sessions by the client random value and decrypt the traffic. You should now see the plaintext HTTP/2 or HTTP/3 requests and responses that were previously encrypted.

Troubleshooting

No patterns matched: The byte pattern is version-specific. If Signal updates, the patterns may no longer match. Re-run BoringSecretHunter on the new library version to extract updated patterns.

Frida can’t attach: Ensure frida-server is running as root on the device (adb shell "su -c '/data/local/tmp/frida-server &'"). Check that USB debugging is enabled and your device appears in adb devices.

Empty ranges from Module.enumerateRanges(): This is the APK mapping issue we discussed. Use scanner.js or the kernel-level approach with Process.enumerateRanges().

Keys extracted but traffic not decrypted: Ensure the capture includes the TLS handshake. Keys only decrypt sessions where you’ve captured the initial handshake. Also verify the key file format is correct (one entry per line, no extra whitespace).

Security Considerations

This technique is not a vulnerability in Signal, BoringSSL, rustls, or any other application. Extracting TLS keys requires privileged access: root on the device, Frida injection capability, and the ability to run arbitrary code. Anyone with this level of access could simply read app memory directly, take screenshots, or log keystrokes—TLS key extraction is just one of many capabilities at that point.

This technique is intended for security research. In malware analysis, it enables researchers to understand how malicious applications communicate with command-and-control servers, even when they use encrypted channels. For privacy auditing, it allows verification of what data applications actually transmit, independent of their stated privacy claims. Security researchers can use it to analyze TLS implementations, study protocol behavior, and identify potential weaknesses. It’s also valuable for solving capture-the-flag cryptography and reverse engineering challenges where traffic decryption is part of the puzzle, as well as for debugging TLS issues in development environments where you control both endpoints.

The fundamental reason this works is that key material must exist in memory during the TLS handshake. This is an inherent limitation of any encryption system running on a compromised host, not a flaw in the cryptographic implementation.

Conclusion

We’ve walked through the complete journey of extracting TLS keys from an Android application with statically linked, stripped TLS libraries. What started as a simple goal—intercepting encrypted traffic—led us through Android’s unconventional library loading, kernel-level memory scanning, binary analysis with Ghidra, and dynamic instrumentation with Frida.

The workflow we developed follows a clear progression: first, identify which libraries contain TLS functionality using memory scanning with scanner.js. Then, extract those libraries using findBoringSSLLibsOnAndroid.py. Next, analyze them with BoringSecretHunter to extract byte patterns for the key logging function. Finally, use friTap with those patterns to intercept TLS keys at runtime, and combine them with captured traffic in Wireshark.

This approach enables security researchers to analyze encrypted traffic from applications that would otherwise be opaque. While the specific patterns we extracted are for Signal 7.52.2 on ARM64 Android, the methodology applies to any application using statically linked BoringSSL or rustls—and the same conceptual approach extends to any TLS library on any platform that Frida supports.